I lit out from Ulaan Baatar with a fresh transit visa for Russia; the numerous small delays of the past month had left me with a scant few days to explore Mongolia, re-enter Russia and enter Kazakhstan. A quick taxi ride to the Russian embassy, and two days later (and US$250 lighter) I had two more weeks to head south to the Gobi, then northwest to the Olgii region, and the Altai.

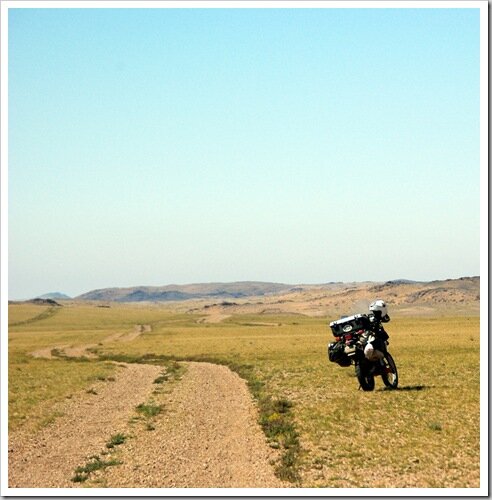

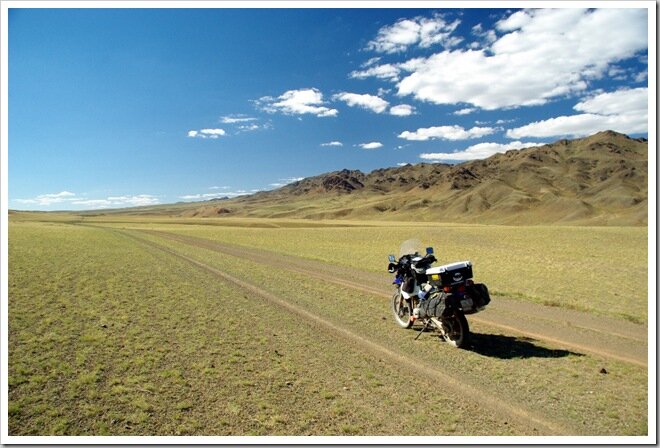

The paved road runs out about 20 miles south of UB, and and it would be six days before my tires touched tarmac again. Where the pavement ends, the tracks begin: 2 or 8 or more sets of tracks worn into the grassy landscape, some merging into others, some leading off into the hills for small villages or gers that may no longer be there. At some point I was diverted from the main track and found myself on a lone and little-used two-wheeled track was headed in the right direction (that is, south-southwest toward Mandalgov), meandering across the steppe with the casual line of a dropped rope.

Rounding a blind bend I surprised an eagle who lifted off impossibly on a 6-foot wingspan. Standing up on the pegs, in 2nd gear, the bike working easily over the undulations and across dry streambeds, having a dual-sporting delight until I found myself carrying too much speed and entering deep sand. The front end squiggled, I panicked and when the front wheel hit the raised edge of the track I was flicked off the bike like a dry booger, coming down hard on my left shoulder. No damage to me, but the bike’s windshield broke at the two upper mounting points. Three feet of duct tape made a temporary repair, and once the adrenaline went away I was off at a more sedate pace.

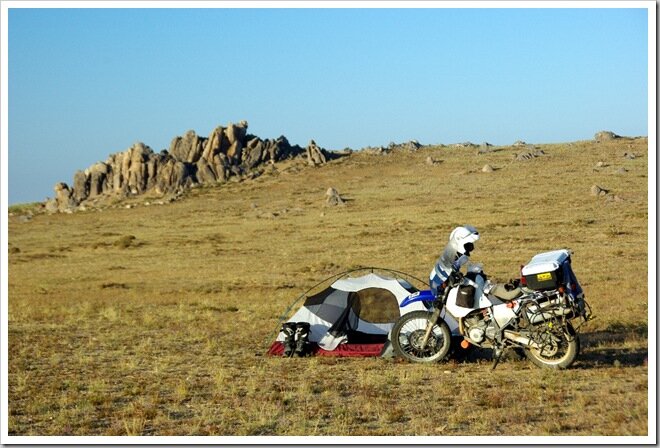

Mongolia is a camper’s delight. Throw a dart at a map of Mongolia, and wherever it sticks is probably a good place to pitch a tent.

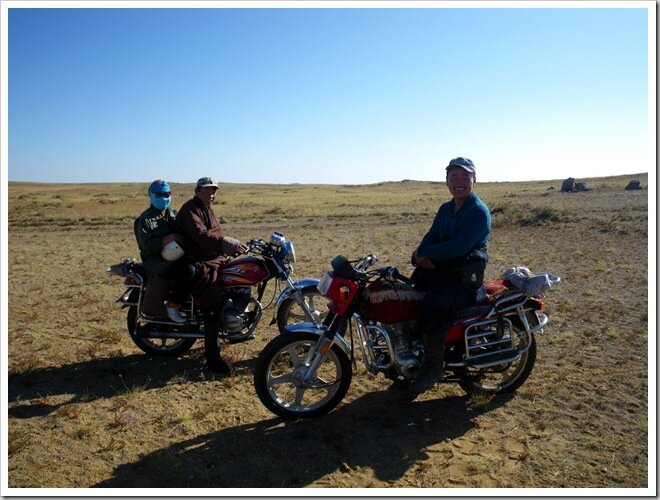

No matter how far off the beat track you think you are, eventually a Mongolian or three will pop by to see what’s up.

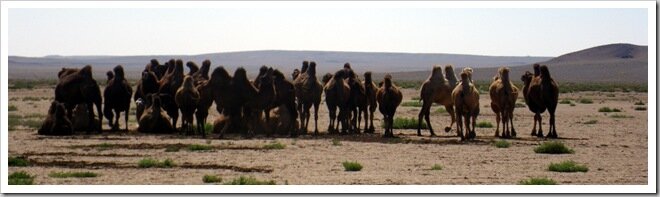

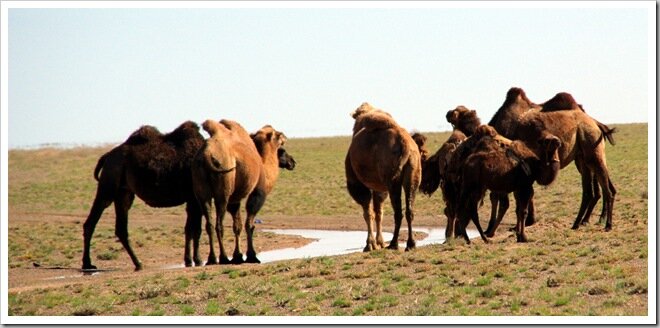

I rarely saw motorcycles in UB, but out in the countryside there were four motorcycles to every four-wheeled vehicle. When a herder stopped by the campsite, we’d start with “Sain baina uu?” (“How are you?”), and then continue with hand gestures, writing in the sand (great for numbers), or I’d whip out the map and we’d discuss where I’d come from and where I was going. The fellow on the right was out checking on his herds of camels, goats, and sheep. And on the 2nd day, I was rewarded with a sighting of Bactrian (two-humped) camels.

But in truth, I smelled them long before I saw them. I can only imagine the smell of a camel market where hundreds if not thousands of these odoriferous critters are milling about.

On the third day I entered Gurvan Saikhan National Park for what would be the most challenging two days of riding of my life. Miles of dry riverbed (up on the pegs, pull back on the bars, stay on the throttle, goose it if she starts to get squirrelly), go-fast alluvial plains, occasional single-track to go around rocky lava beds, and a few steep ravine climbs that had me cresting the top with my heart in my throat. Loss of traction, a wheelie or stalling would have had me rag-dolling to the bottom followed by a a 350-lb motorcycle, and a noisy cascade of my trip’s gear.

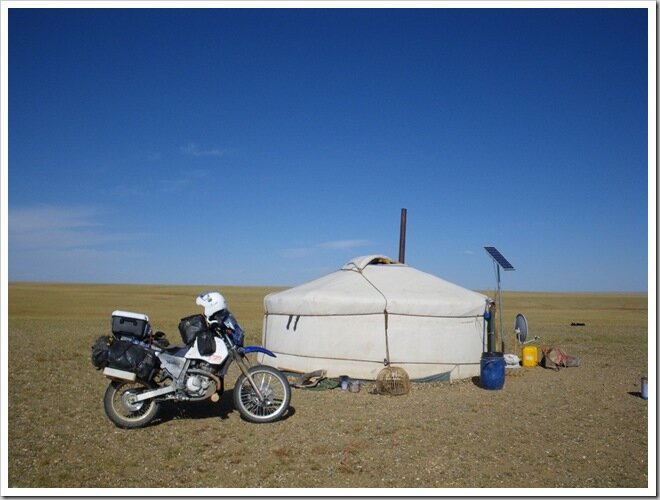

Around mid-morning, heading north out of the national park, I met a herder who was taking a break next to his motorcycle on the side of the road. We chatted, and he asked if I’d like to see his ger. (He asked by pointing to the phrase in the Language section of my LP guide.) After stopping at a well and topping off a huge water barrel and lashing it to his bike’s pillion seat, we went cross-country to his ger, where we were greeted by a dog and a bored horse.

Upon entering the ger he pulled out a small wooden stool and motioned for me to have a seat. Then he lit the central stove with clods of dry dung, and placed a large steel bowl in an opening in the top. To the bowl he added water and a fistful of loose tea, and with more dung fuel brought the mixture to the boil, then added a few cups of mare’s milk. He served it up in small porcelain bowls, him sipping away at the scalding mixture right away, while I passed it from hand to hand trying not to burn my fingers or spill it or look too much like a tender first-worlder.

Next he emptied and wiped out the steel bowl, added more water and brought it to boil. From under a bed he pulled out a pile of cloth-swaddled butchered meat and carved off a few ribs and a foreleg of mutton, and dumped it all into the boiling water. After the meat had boiled for a few minutes he added handfuls of small potatoes and salt, and when it was all cooked the meat & potatoes were placed into a separate large dish. We sat on the floor, carving away and eating the meat and fat and potatoes (he made sure I got the foreleg), sipping more mare’s milk tea, and watched sumo wrestling highlights on his solar-powered, satellite-fed television set. (The Mongolian sumo champ lost to a gargantuan towering sumo’d-up westerner!)

From the meat and potatoes broth he made salty rice soup, and while slurping it up we watched Greco-Roman wrestling championships (Mongolia won), and after a snort of snuff I went on my way, thanking him for the meal and hospitality.